Time and again, I have spoken about API integrations, and each time I find an improvement from the last, once more into the fray.

I was recently tagged on twitter about an article called SDKs, The Laravel Way. This stood out as it somewhat mirrored how I do API integrations and inspired me to add my own two cents.

For the record, the article I mentioned is excellent, and there is nothing wrong with the approach taken. I feel like I can expand upon it a little with my lessons learned in API development and integrations. I won't directly copy the topic as it is for an API I am not familiar with. However, I will take concepts in an API I am familiar with, the GitHub API, and go into some details.

When building a new API integration, I first organize the configuration and environment variables. To me, these belong in the services configuration file as they are third-party services we are configuring. Of course, you do not have to do this, and it doesn't really matter where you keep them as long as you remember where they are!

// config/services.php return [ // other services 'github' => [ 'url' => env('GITHUB_URL'), 'token' => env('GITHUB_TOKEN'), 'timeout' => env('GITHUB_TIMEOUT', 15), ],];The main things I make sure I do is store the URL, API Token, and timeout. I store the URL because I hate having floating strings in classes or app code. It feels wrong, it isn't wrong, of course, but we all know I have strong opinions ...

Next, I create a contract/interface - depending on how many integrations will tell me what sort of interface I may need. I like to use an Interface as it enforces a contract within my code and forces me to think before changing an API. I am protecting myself from breaking changes! My contract is super minimal though. I typically have one method and a doc block for a property I intend to add through the constructor.

/** * @property-read PendingRequest $request */interface ClientContract{ public function send();}I leave the responsibility of sending the request to the client. This method will be refactored later, but I will go into detail later. This interface can live wherever you are most comfortable keeping it - I typically keep it under App\Services\Contracts but feel free to use your imagination.

Once I have a rough contract, I start building the implementation itself. I like to create a new namespace for each integration I build. It keeps things grouped and logical.

final class Client implements ClientContract{ public function __construct( private readonly PendingRequest $request, ) {}}I have started passing the configured PendingRequest into the API client, as it keeps things clean and avoids manual setup. I like this approach and wonder why I didn't do this before!

You will notice I still need to follow the contract, as there is a step I need to take beforehand. One of my favorite PHP 8.1 features - Enums.

I create a method Enum for apps, I should make a package, as it keeps things fluid - and again, no floating strings in my application!

enum Method: string{ case GET = 'GET'; case POST = 'POST'; case PUT = 'PUT'; case PATCH = 'PATCH'; case DELETE = 'DELETE';}I keep it simple to start with and expand when needed - and only when needed. I cover the main HTTP verbs I will use and add more if needed.

I can refactor my contract to include how I want this to work.

/** * @property-read PendingRequest $request */interface ClientContract{ public function send(Method $method, string $url, array $options = []): Response;}My clients' send method should know the method used, the URL it is being sent to and any needed options. This is almost the same as the PendingRequest send method - other than using an Enum for the method, this is on purpose.

However, I do not add this to my client, as I may have multiple clients that want to send requests. So I create a concern/trait that I can add to each client, allowing it to send requests.

/** * @mixin ClientContract */trait SendsRequests{ public function send(Method $method, string $url, array $options = []): Response { return $this->request->throw()->send( method: $method->value, url: $url, options: $options, ); }}This standardizes how I send API requests and forces them to throw exceptions automatically. I can now add this behavior to my client itself, making it cleaner and more minimal.

final class Client implements ClientContract{ use SendsRequests; public function __construct( private readonly PendingRequest $request, ) {}}From here, I start to scope out resources and what I want a resource to be responsible for. It is all about the object design at this point. For me, a resource is an endpoint, an external resource available through the HTTP transport layer. It doesn't need much more than that.

As usual, I create a contract/interface that I want all my resources to follow, meaning that I have predictable code.

/** * @property-read ClientContract $client */interface ResourceContract{ public function client(): ClientContract;}We want our resources to be able to access the client itself through a getter method. We add the client as a docblock property as well.

Now we can create our first resource. We will focus on Issues as it is quite an exciting endpoint. Let's start by creating the class and expanding on it.

final class IssuesResource implements ResourceContract{ use CanAccessClient;}I have created a new trait/concern here called CanAccessClient, as all of our resources, no matter the API, will want to access its parent client. I have also moved the constructor to this trait/concern - I accidentally discovered this works and loved it. I am still determining if I will always do this or keep it there, but it keeps my resources clean and focused - so I will keep it for now. I would love to hear your thoughts on this, though!

/** * @mixin ResourceContract */trait CanAccessClient{ public function __construct( private readonly ClientContract $client, ) {} public function client(): ClientContract { return $this->client; }}Now that we have a resource, we can let our client know about it - and start looking toward the exciting part of integrations: requests.

final class Client implements ClientContract{ use SendsRequests; public function __construct( private readonly PendingRequest $request, ) {} public function issues(): IssuesResource { return new IssuesResource( client: $this, ); }}This enables us to have a nice and clean API $client->issues()-> so we aren't relying on magic methods or proxying anything - it is clean and discoverable for our IDE.

The first request we will want to be able to send is listing all issues for the authenticated user. The API endpoint for this is https://api.github.com/issues, which is quite simple. Let us now look at our requests and how we want to send them. Yes, you guessed it, we will need a contract/interface for this again.

/** * @property-read ResourceContract $resource */interface RequestContract{ public function resource(): ResourceContract;}Out request will implement a concern/trait that will enable it to call the resource and pass the desired request back to the client.

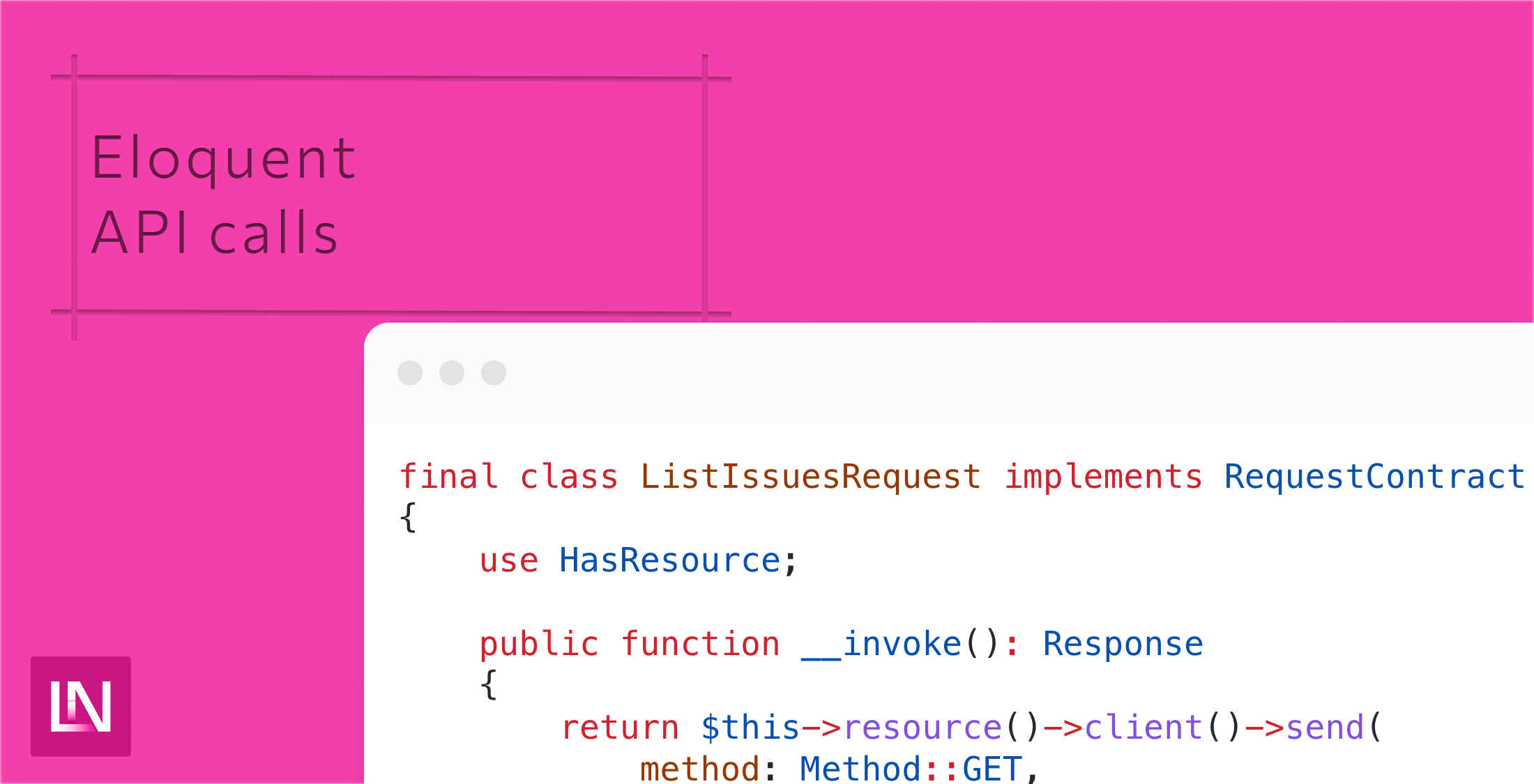

/** * @mixin RequestContract */trait HasResource{ public function __construct( private ResourceContract $resource, ) {} public function resource(): ResourceContract { return $this->resource; }}Finally, we can start thinking about the request we want to send! There is a lot of boilerplate to get to this stage. However, it will be worth it in the long run. We can fine-tune and make changes at any point of this chain without introducing breaking changes.

final class ListIssuesRequest implements RequestContract{ use HasResource; public function __invoke(): Response { return $this->resource()->client()->send( method: Method::GET, url: 'issues', ); }}At this point, we can start looking at transforming the request should we want to. We have only set this up to return the response directly, but we can refactor this further should we need to. We make our request invokable so that we can call it directly. Our API now looks like the following:

$client->issues()->list();We are working with the Illuminate Response to access the data from this point, so it has all the convenience methods we might want. However, this is only sometimes ideal. Sometimes we want to use something more usable as an object within our application. To do that, we need to look at transforming the response.

I am not going to go into too much here with transforming the response and what you can do, as I think that would make a great tutorial on its own. Let us know if you found this tutorial helpful or if you have any suggestions for improving this process.