The story usually goes something like this: there’s a huge project at work. Maybe it’s the company’s first big client. It could be a “the future of the business is hinging on this” situation. This high-pressure time comes with almost impossible deadlines and, as a result, a lot more little mistakes get pushed through. As the project progresses, new problems present themselves which means more work added on.

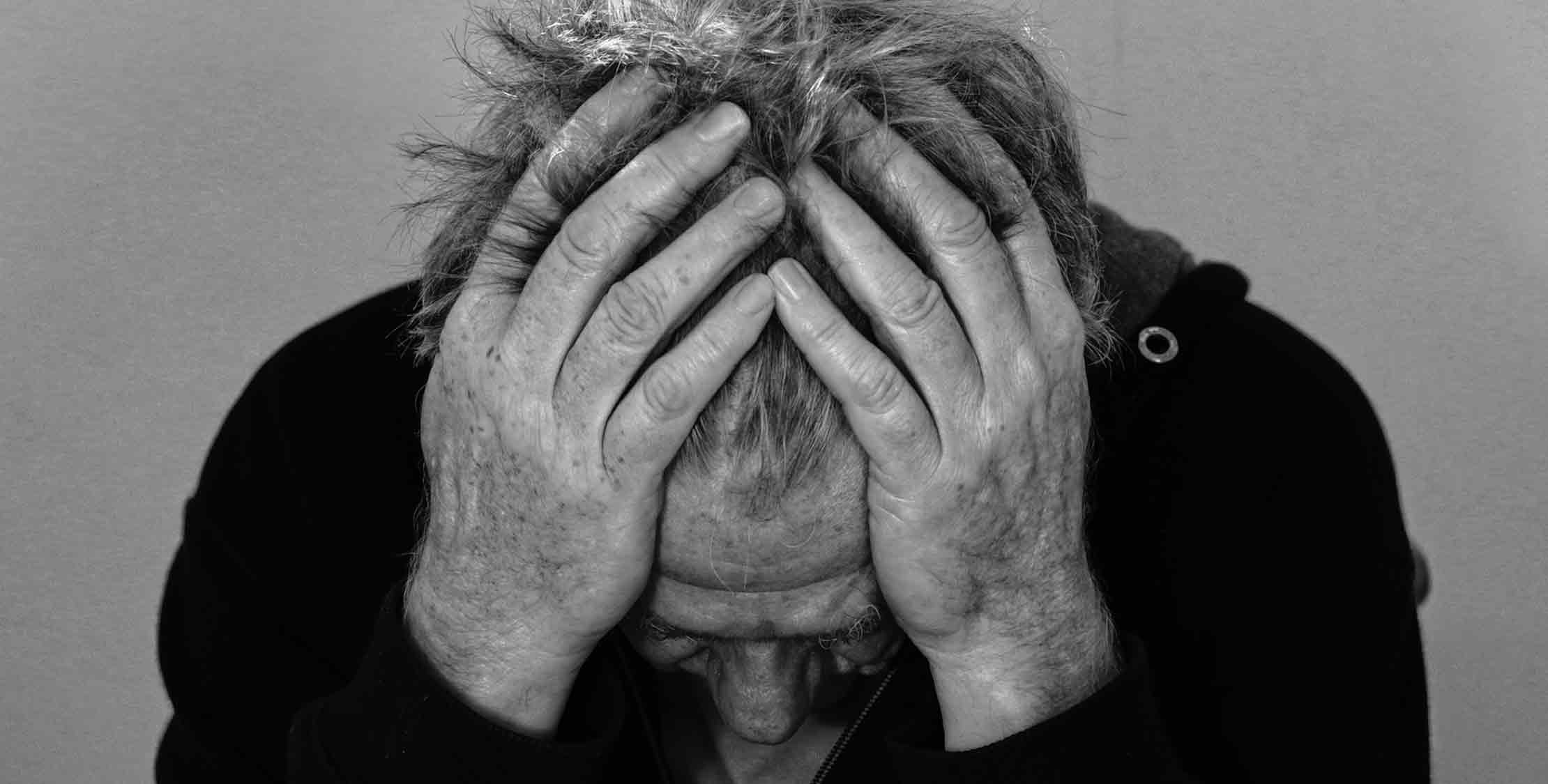

As the workload increases and the time away from work decreases, you become disengaged. Settling into apathy is your new normal. You don’t care if the work gets done well or not; you just go through the motions because that’s your job. Six months, seven-day-a-week work schedules and 16+-hour-workdays later, your eye starts twitching. You’ve developed other health issues as a result of extreme stress. Those bad feelings seep into your home life, and you stop talking to your wife or reading to your kids. Then one day, it all comes to a head: you don’t know if you can ever spend another day as a developer again. You’re completely burned out.

Burnout for developers is common. Devs spend all day in a very critical, intellectually taxing job. You often take work home which means you are staring at glowing screens for upwards of 14 hours a day. To deal with the burnout, many devs take breaks from working. For some, that’s three months. For others, it’s two years. And for a select few, they left the industry completely. Their burnout and the experience surrounding it was so severe that they changed careers.

How did things get this bad?

When people start becoming disengaged with their work and feel a general sense of apathy, that is a precursor to burnout popularly called brownout. Brownout is the caution zone because the person experiencing it isn’t yet in an all-out crisis. They are experiencing some disengagement, but are still performing at a high level.

Brownout is extremely common in our smartphone-obsessed, post-recession world of work. The jobs eliminated in the aftermath of 2008 still needed to get done, so employers tasked their remaining employees with completing the extra work. Unfortunately, there was rarely an increase in pay and an almost crippling fear of taking a vacation when needed. Brownout became the norm.

But what does this look like in tech? Specifically, for developers. Many devs spend their days working on fixing problems that come up in code. It can get boring, tedious and not provide enough of a challenge. With hours piling up and the work itself not changing, boredom turns to disengagement. That turns to brownout and, slowly, burnout.

To add to the problem, few people are brave enough to say they’re having trouble. Since many developers identify as introverts, they have a difficult time discussing what’s going on with themselves emotionally. There’s also the stigma associated with any sort of mental disability – including the feeling of mental collapse and overwhelm that comes with burnout. The fear of being pegged as “difficult” or “weak” to potential employers keeps a lot of people silent on their struggle.

You know what else doesn’t help? People bragging about how many hours they work. Not only is this irresponsible and unhealthy, it’s unrealistic and harmful. Here’s why: people maintaining in a brownout immediately feel weak when they hear another person talk about working more hours than they do. And you know what happens next. That person works more. The feelings of overwhelm intensify. Then? Burnout.

The truth is any normal person working 130 hours in a seven-day span can’t maintain that without significant stress. No matter how much they love their job or how much they believe in the company, they will eventually find themselves in a catatonic burnout haze.

So what can we do to avoid burnout? Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at beating burnout with exercise and discuss the science behind it and the role exercise plays in defeating the demon.

Sharon is an empathy consulting, public speaker and writer. She has over a decade of experience creating and managing content for businesses. A lifelong stutterer, she utilizes her experiences with her speech along with her background in marketing to help companies communicate more effectively both internally and with their target audience. She writes and speaks about improving communication through empathy. She lives in Pittsburgh.