GitHub has been rolling out Kubernetes over the last year on github.com. I find beautiful irony in the fact that GitHub hosts the source code for so many popular open source projects.

Think about it.

GitHub hosts Ruby, Rails, MySql, and many other open-source repositories, and then turns around and uses those technologies to build—GitHub. It’s “dogfooding” to the extreme.

Over the last year or so, GitHub has been experimenting with and integrating Docker containers with Kubernetes. Kubernetes is “is an open-source system for automating deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications.”

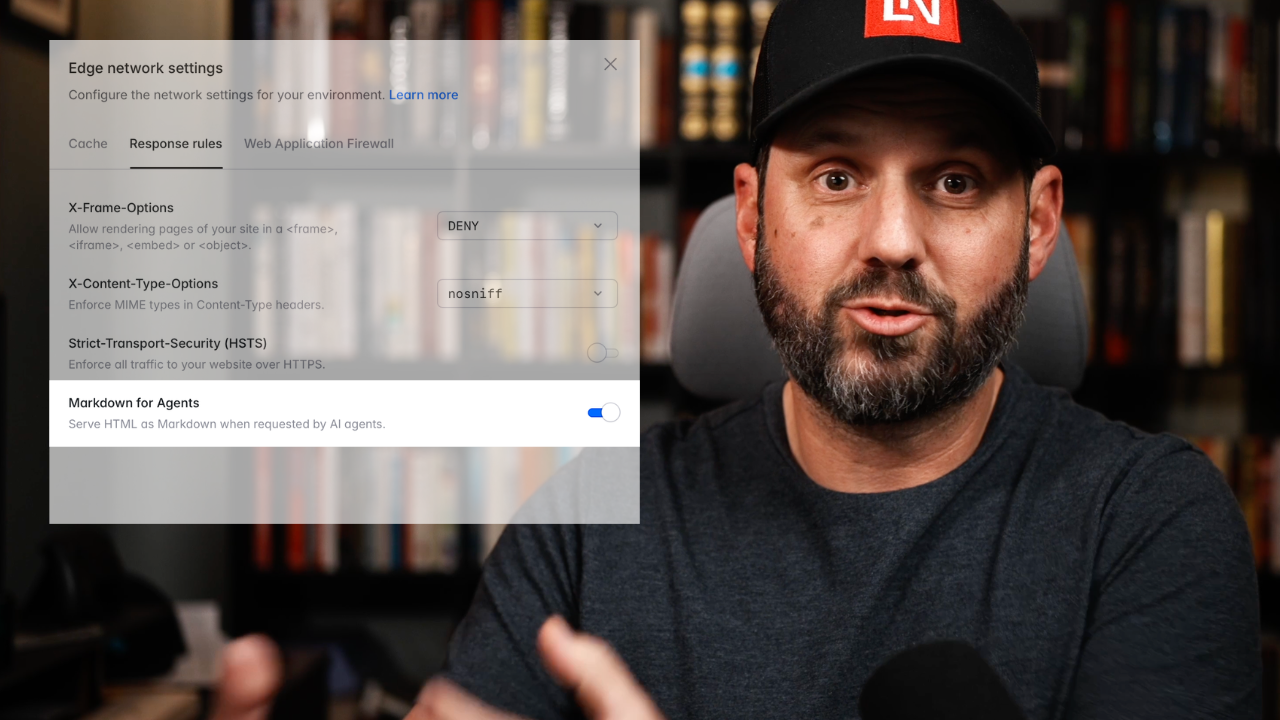

Over the last year, GitHub has gradually evolved the infrastructure that runs the Ruby on Rails application responsible for github.com and api.github.com. We reached a big milestone recently: all web and API requests are served by containers running in Kubernetes clusters deployed on our metal cloud. Moving a critical application to Kubernetes was a fun challenge, and we’re excited to share some of what we’ve learned with you today.

GitHub’s adoption is huge for containerization and Docker movement. Organizations of massive scale are moving critical applications to containers to create a more resilient and reliable infrastructure. It seems as though GitHub’s move to container orchestration has increased the ability for more of a self-service platform with less strain on operations and Site reliability engineers (SREs). One huge benefit is insulating an application from differences between environments.

Previously, it seems as though GitHub relied on Capistrano to deploy code to all frontend application servers. Deployment is accomplished with SSH connections to each server where code is updated and services restarted. If a rollback is needed, Capistrano SSH’s into each server and moves a symlink to a previous version.

In a traditional application server environment, when you need additional application nodes you must provide configuration management tools to provision servers. Once servers are ready, you then deploy code on them through a tool like Capistrano, and then finally move them into place to accept traffic. I know from personal experience that expanding the pool of nodes and rolling back code versions can be cumbersome in a traditional server environment. I don’t have an intimate knowledge of GitHub’s infrastructure and deployment process; I can only speak from my own experience in how I was scaling services before I started using Docker.

Since Docker images produce a single code artifact, rolling back from a bad release is usually much smoother. Kubernetes takes care of rolling back to the desired state. Plus, you can run a bad version in another environment in a repeatable way to further isolate issues.

Now, all web (github.com) and API (api.github.com) requests are served from containers running in Kubernetes on GitHub’s metal cloud.

Read all about the journey on GitHub’s engineering blog.